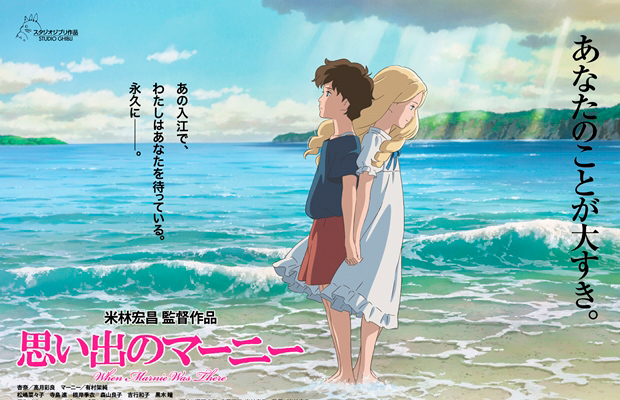

As we conclude our coverage of the Annecy International Animation Festival, we’ll be focusing on the most beloved animation company in all of Japan: Studio Ghibli. When Marnie Was There is possibly the final film to be released from the prolific studio, you have to think about what has made this company so special compared to the American heavy-hitters. There are several animation fans who love Ghibli beyond the likes of Disney and Pixar for the iconic, breathtaking animation, reflective atmosphere, and the moral complexity ingrained into every one of their films.

When Marnie Was There is indicative of so much of what the company stands from the English origin, the female protagonist, and the relatable themes of maturation and isolation. But it’s surprising this film is not from the mind from Hayao Miyazaki or Isao Takahata. Instead, the film’s creation was brought about by Hiromasa Yonebayashi, who previously worked with Ghibli before creating The Secret World of Arrietty. This leaves us anime fans in a quandary, wondering if When Marnie Was There is worthy of being Studio Ghibli’s swan song.

We have to face facts. The founders of Ghibli including the two iconic directors and producer Toshio Suzuki, are all in there 70s. Miyazaki and Takahata have wanted to retire for years now, but they have a cultural, workaholic mentality that keeps them in the industry. Anime would not have the same worldwide reputation if not for these titans of the craft. But there’s an uncomfortable aura when you look at the studio in a new lens upon seeing the fascinating documentary, The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness.

The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness is a fly-on-the-wall style documentary, observing the life of Hayao Miyazaki as he was creating The Wind Rises. It’s an engaging, beautiful look at the development of Studio Ghibli from the very beginning, where we see the enigmatic Miyazaki start as a meticulous mangaka and television director overseeing Heidi: Girl of the Alps and Lupin the 3rd. He would then become the Walt Disney-level icon after forming the animation studio with the other star of the film, Toshio Suzuki. Suzuki’s dedicated patience as a producer and PR skills has allowed Ghibli to flourish despite their constant delays and bizarre approach to filmmaking.

This film is a goldmine to understanding  what makes Miyazaki’s films unique. The biggest revelation I had while watching the movie was discovering that Miyazaki does not write scripts. He only creates storyboards and has his associates cobble together a story from what he draws. It explains so much about why his films have those specific flourishes of pacing and character development. Hayao’s dedication to work is balanced by his schedule of exercise, photography, enjoying nature, and waving to members of the local nursery and his staff.

what makes Miyazaki’s films unique. The biggest revelation I had while watching the movie was discovering that Miyazaki does not write scripts. He only creates storyboards and has his associates cobble together a story from what he draws. It explains so much about why his films have those specific flourishes of pacing and character development. Hayao’s dedication to work is balanced by his schedule of exercise, photography, enjoying nature, and waving to members of the local nursery and his staff.

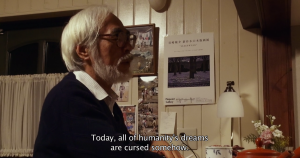

On the other hand, what’s heartbreaking to learn is how Miyazaki himself is a bitter curmudgeon with a pretty bleak disposition of the future. For being one of the biggest visionaries on the genre, he feels animation have changed from being artistic visions to “grand hobbies” that are celebrated primarily by otaku. He is convinced that Ghibli will sink when he is gone. The most startling example of this is the treatment of his son, Goro Miyazaki, who does not meet up to his father’s standards. Sadly, Goro is never interviewed in the film. Taking out Miyazaki, the writing is on the wall for Ghibli to fade if drastic changes do not happen.

On the other hand, what’s heartbreaking to learn is how Miyazaki himself is a bitter curmudgeon with a pretty bleak disposition of the future. For being one of the biggest visionaries on the genre, he feels animation have changed from being artistic visions to “grand hobbies” that are celebrated primarily by otaku. He is convinced that Ghibli will sink when he is gone. The most startling example of this is the treatment of his son, Goro Miyazaki, who does not meet up to his father’s standards. Sadly, Goro is never interviewed in the film. Taking out Miyazaki, the writing is on the wall for Ghibli to fade if drastic changes do not happen.

Watch with subtitles. It isn’t the trollish meme, but it is not that far off.

I was a tad unsatisfied seeing how the film treated Isao Takahata, who has created films on Miyazaki’s level with Grave of the Fireflies and my personal favorite, Pom Poko. Miyazaki comments that while friendly rivalry with his fellow co-creator, he’ll turn around in another scene and claim: “Takahata is not a director.” He’s nearly missing from the film because The Tale of Princess Kaguya took eight years to make at a different location thanks to the ambitous art style and overblown budget. But there’s a reoccurring theme with both these films, including When Marnie Was There.

All three of these films are slated to be the final animated movies from their directors. We understand that Miyazaki and Takahata want to stop due to age. However, the 44-year-old Yonebayashi has decided to stop working for Ghibli for unexplained reasons. Yonebayashi has stated he wants to continue to making films, but in “light-hearted, action-fantasy” type of direction. And I hope him all the best with his new career, because as much as When Marnie Was There fits all the constraints of what makes a great Ghibli movie, it is sadly a disappointment.

All three of these films are slated to be the final animated movies from their directors. We understand that Miyazaki and Takahata want to stop due to age. However, the 44-year-old Yonebayashi has decided to stop working for Ghibli for unexplained reasons. Yonebayashi has stated he wants to continue to making films, but in “light-hearted, action-fantasy” type of direction. And I hope him all the best with his new career, because as much as When Marnie Was There fits all the constraints of what makes a great Ghibli movie, it is sadly a disappointment.

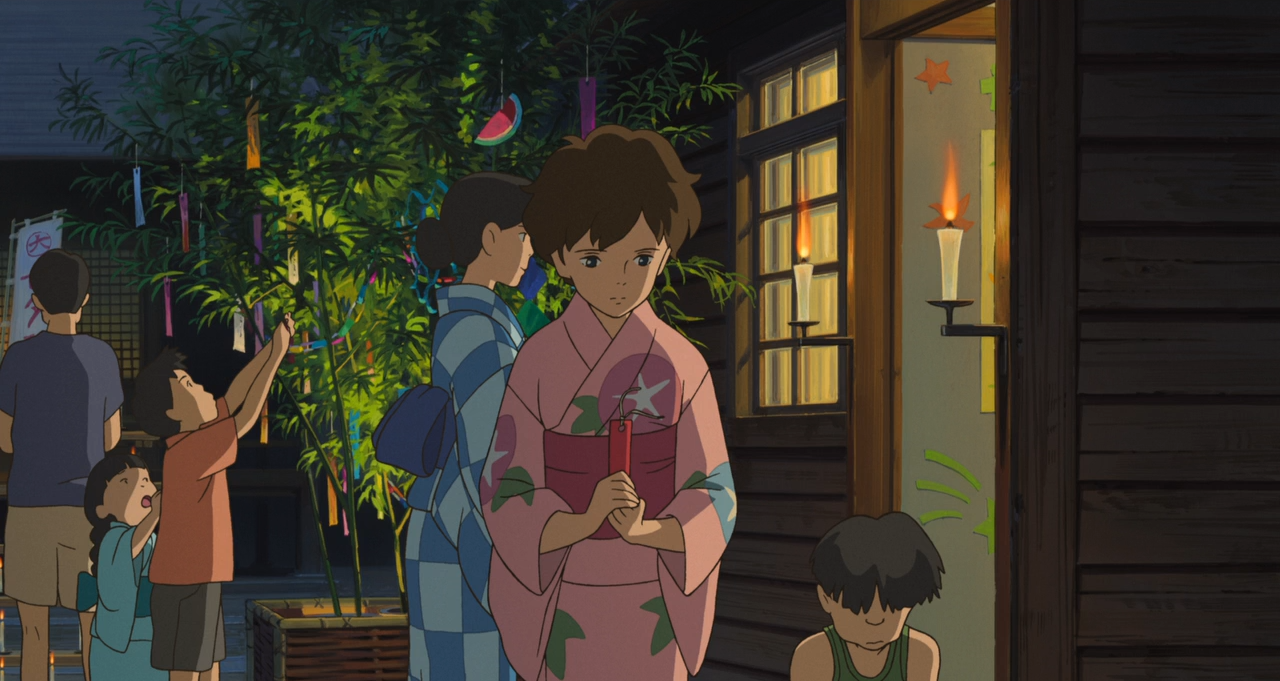

When Marnie Was There is based on a 1967 young adult novel by the same name, following the adventures of Anna, a 12-year-old foster child with asthma. She’s taken to Hokkaido, as her family believes the country air will help her ailment, but she still has trouble connecting with girls her age. Yet, she is drawn to this mysterious mansion located at the nearby marsh, where she encounters the beautiful, enchanting Marnie who she develops a deep connection with. As the two grow closer together, Anna slowly starts to discover Marnie’s tumultuous history.

I never watched The Secret World of Arrietty, as I was already familiar with the book the film is based on, The Borrowers, but I feel much of the issues with When Marnie Was There are correlated with the source material, as the YA-feel is incredibly apparent. Anna is perhaps the most uninteresting Ghibli protagonist ever, as she’s only defined by her perpetual angst and teenaged-fueled indifference. Her instrinsic characteristics are centered only on her illness and her artistic talents, but she has a complete lack of personality aside from her relationship with Marnie. Anna’s rebellious nature is grating because her environment is totally supportive to her situation, no matter how dangerous it becomes.

The oddest thing about this film is that the first half feels very much like a supernatural harlequin romance. Marnie single-handedly carries the film, because her amazing, caring attitude makes the movie relatively fascinating. This is startlingly noticeable as Anna constantly broods about how ugly and dismissive she is, compared to her beautiful, foreign counterpart. When the film has lines like “You are my perfect secret” and “You are the most important girl I’ve ever known;” the quasi-romantic tone feels intentional.

All the trademarks to what makes Ghibli films recognizable and magical are here in spades. The animation is gorgeous with an incredible emphasis on the Hokkaido scenery, especially the marsh. As the film unveils more about the past, the artists put in an extraordinary amount of effort to make every scene match it’s time period, even with the mansion’s shifts between pristine and dilapidated. Anna’s life with her foster mother’s relatives is comfortably quaint, with the iconic, realistic charm of having down-to-earth tertiary characters performing mundane activities.

The movie is also painfully back-loaded, with most of the revelations occurring in the last quarter. Marnie’s story is very gripping as most of her interactions with Anna parallel her life in the past. We’re left with a situation like the film Julie & Julia where the inspirational tale about the character in the past is great, but our main character is painfully dry. I could appreciate with what Yonebayashi was aiming for as he detailed the plot to us, but Anna’s growth throughout the movie is underwhelming in the big picture.

There’s also the issue of most of the present-day drama is escalated beyond a relatable point. Despite the fact Anna gets lost or is rescued after she passes out at night, her caretakers ignorantly do nothing to keep her safe or scold her for her actions. You really lose some of the sympathy for her when she screams “fat pig” at a teenage girl after she makes an unassuming comment about Anna’s blue eyes. I imagine Anna’s burdens will resonate better with other foster children, but her overall bland, bleak outlook overpowers her personal motives.

When Marnie Was There pales in comparison to most of Ghibli’s catalog. If you love Ghibli’s classic art style, it is worth watching for the impeccable design yet lacks any breathtaking, fluid moments. I have to agree with other critics who said that Yonebayashi is great at replicating the aesthetics of the studio but lacks the character and story depth to evolve beyond the typical source material. This is for die-hard completionists of Ghibli, because while it is not bad, I don’t see this being anyone’s favorite movie.

My Arbitrary Rating for When Marnie Was There: 5 out of 10 Juicy Ripe Tomatoes.

After watching this movie, I really don’t want Ghibli to stop here. They deserve a better movie to cap off their legendary filmography that inspired so many of us to love Anime. Studio Ghibli has a very small workforce slightly above 50+ people, but I would really like to see another person take the mantle. Miyazaki himself doesn’t think Goro is up to the challenge, but it’d be great if we could see the vision of another lesser-known creator like Yoshifumi Kondō’s Whisper of the Heart or Hiroyuki Morita’s The Cat Returns. I’d even love it if Ghibli used a snazzy, outside director such as Mamoru Hosada (The Girl Who Leapt Through Time/Summer Wars) or Shinichirō Watanabe (Cowboy Bebop/The Animatrix) to help the studio evolve into the modern age.

Even though I may have not sold you on When Marnie Was There, it is absolutely worth watching The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness. There is no more intriguing look into the mind of a creative genius who watches in ire as the genre he creates changes in new directions. The influence of Studio Ghibli is beyond measure, but I don’t believe it is ready to quietly fade into that good night. Let’s keep this pillar of creative talent alive so it inspires our current and future generations.

My Arbitrary Rating for The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness: 9 out of 10 Declarations of Finality.

Thank you so much for following Animated Anarchy this entire week as we have covered foreign films. What would you like to see return as this article is back to a weekly basis? More singular film reviews? Expanded coverage of American cartoons? Lists of recommendations? Leave a comment below, share the content, and keep the anarchy flowing!