Vince marks the return of Heavy Meta with a discussion on whether the ability to bench press a bus or smell a man’s cologne from three floors down gives a hero the right to make decisions for others.

It’s a trope as old as time: the hero, fearing for the safety of their loved ones, wilfully withholds information or otherwise keeps them out of the line of fire when it’s time to dealing with their villainous foes. It comes from the best intention: the desire to adhere to that old adage about the correlation between power and responsibility. It would be irresponsible to put “innocent bystanders” in danger without them being equipped to deal with (or even survive) it, right?

The focus of today’s Heavy Meta isn’t necessarily that the hero is wrong in thinking their family or friends would be safer not knowing or not being involved in the central conflict, but rather, whether the power to generate energy shields, shoot fire, or smell a man’s cologne from three floors down also gives them the authority to make decisions for other people. A number of different storytellers ( the minds behind Steven Universe, the Dresden Files books, and the recent Daredevil series among others) have begun questioning the assumption that being the hero gives them the right to make that call. The result is a blurring of the line between the active hero and the passive bystander, and even challenging us to re-define our concept of heroism in general.

Soapbox Damsels

The problem that many have with the trope of “It’s too dangerous; stay here” and its ilk is one of agency. When a hero vetoes the desire of a secondary character to actively participate in the events, by sharing information, supporting them emotionally or pragmatically, it robs that character of a voice and relegates them to being an objective or goal for the hero to protect, worry about, save, or become motivated by if they die.

If this is sounding familiar, it’s because Anita Sarkeesian addressed a similar issue with women in video games on her Tropes vs. Women YouTube series. In it, she gives multiple examples of how female characters are reduced to trophies, victims, or plot devices instead of being actual people with motives, beliefs, and agency independent of male protagonists.

Sarkeesian’s video is relatively recent, but it reflects a trend in media that has been going on for some time, as the characters who often get the “stay in the car” treatment are women who, you guessed it, are cast in the role of the hapless bystander. Predictably, this resulted in an outcry from fans who wanted to see women be treated as people instead of mannequins with “KEEP ALIVE” emblazoned across their foreheads. You’re likely familiar with the progression of media from there, with more women being cast in starring roles, being shown as a capable of saving themselves and others, and otherwise having a rich inner story not dependent on the needs of male characters.

Less talked about is how characters in minority roles have been given a similar role in 20th century media. This is largely due to the fact that until the early 60s, it was rare to see a minority character cast as anything but the villain (or the subject of a cheap, racist joke). Even as ethnic diversity crept into the ranks of the good guys in the seventies, minority characters were largely kept to sidekick/supporting/minor roles.

In fact, even in 2015 people react with vitriol (or at least skepticism) when a cast attempts to add more women, more blacks, or more diversity in general is the classic complaint. The struggle for casts to be more diverse has been just that: a struggle, but characters like Lucy Liu’s Joan Watson in Elementary and Steven Yeun’s Glenn from The Walking Dead are major steps forward in terms of characters who are not defined by their ethnic/cultural background. However, their ability to jump into the fray and assert their own agency makes them exceptions even today. Much of the time, non-white characters are still shunted to the side when its time for the Exciting Adventures of White Man! to take center stage.

More Than Politics

Despite all this, however, Damseling isn’t just a social justice topic. That’s part of it, but only a fragment. On a larger scale, it’s more about how we define what heroism is, and who can and “can’t” be a hero. It’s not said explicitly, but the process of “damselling” categorizes people into a subset, declaring who is and isn’t allowed to take part in actions or decisions deemed “heroic.” The problem isn’t just who gets lumped into the bystander category, but that there are even hard-and-fast categories at all.

The presupposition that the hero/bystander divide reveals is one that defines heroism as something you HAVE, rather than something you CHOOSE to do. Western society tends to view it in much the same way that they do qualities like intelligence or athleticism: you either have it or you don’t: the thing is, in all three cases, they’re wrong. Case in point: Wikus Van Der Merwe.

Heroes are defined by their actions, and the fabulous thing about being a human being is that at any given point, you can choose to do a myriad of different things, even if you’re being STRONGLY contra-indicated to do otherwise. This is why Wikus from District 9 is one of my favorite movie characters: because if we’re honest? He’s kind of a shitbag. More often than not, he’s a coward, he’s a bureaucratic little slug of a pencil-pusher who only got his job because of nepotism. More than once when the chips are down, he harms those who are trying to help him either out of cowardice, desperation, or prejudice. He’s flawed, he’s scared. By the “quality” definition, he’s about as far from a hero as you get.

But when the chips are down, when Christopher Johnson is about to be slaughtered for nothing other than his desire to go home, Wikus decides against all odds to, for the first time in the movie, disregard his own personal goals and run off to defend Christopher and risk his life in the process. He’s terrified, weak, shaking, his voice is cracking. But he DOES IT. He shows that all that separates a witness from a hero is the choice to be the latter.

The Persistence of A Myth

The question remains: we acknowledge that heroes are defined through their deeds, so why has the idea that heroes are of a different, “special” class than the rest of us remained so stubbornly ingrained in our culture? Part of it is, as I mentioned, that just from the way we’re cognitively wired, humans have a real hard-on for categorization. It’s an inevitable consequence of our brains’ attempts to make sense of a world that’s throwing entirely WAY too much crap at it to comprehend on an individual basis. To get a basic idea of how this works, click through the image to the article on Prototype theory below:

I believe that part of why we find comfort in the idea that some of us just aren’t cut out to make the big decisions is the same reason that people will continue to perpetuate governments that mistreat them instead of proactively tearing them down and rebuilding: it relieves some of the burden and responsibility that come with self-governance.

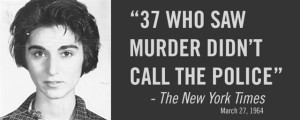

The hero/bystander divide provides security in the ability to avoid a stressful or potentially dangerous situation by rationalizing it as, “I don’t have quality X necessary to intervene here; fortunately, someone else more qualified surely does! I’ll leave it to them.” Problem is, when everyone thinks that a hero is going to swoop down and save the day, no one acts. Kitty Genovese found this out firsthand.

The above event caused so much stir that an abundance of research was done on why every single person failed to act. Since that point, entire journals have come into being that show the effects of crowds and anonymity on people’s behavior. However (and this is where hero/bystander relations com into it), similar amounts of studies exist that show how people’s perceptions of self influence their actions. One famous study showed that, for example, when people could see themselves in a mirror, it dissuaded cheating by making their individual concept more salient.

The takeaway from this? The sword cuts both ways. When society stops perceiving heroes and bystanders to be distinctly different TYPES of people, it gives the common man more power to have their voice heard and their wishes respected. However, the fact that their voice can now impact the world at large with greater force burdens them with a greater level of responsibility for how that freedom is used. To whom much is given, much is required.

This might seem a bit heavy for talking about a show about magical space lesbians or a superhero whose superpower is that he’s a blind guy who can see, but art is a way to see the values of society reflected back at us. If we want to change those values (and understand the implications of those changes), we could do a lot worse than taking a look at the kinds of philosophy that populate our entertainment.

Vince Smith is a writer, podcast host, and dyed-in-the-wool geek of all trades. You can check out reviews and his Let’s Play series, Cupcakes & Lighter Fluid over at The Rogues’ Gallery. He is also the Corner Man for the Inside the Locker podcast, breaking down the latest fights from the MMA world.

1. The notable exception here is the Blaxploitation movement, but the key there is the ‘sploitation’ part. Ethnic characters were an exotic novelty, and so long as they were kept in their “appropriate” niche (black characters as pimps or streetwise gangsters, East Asians as martial artists), people were fine with it. Things have improved, but the problem is still prevalent.

-Written by Vincent Mendoza