“You wanna see sumtin’ REAL scary?”

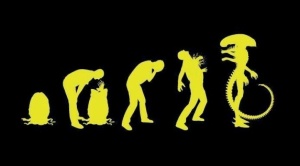

With All Hallow’s Eve right around the corner, Vince turns his ghoulish gaze towards what the best recipe for a truly terrifying movie monster is. The answer: a pinch of the unknown, a dash of expectation violation, and just a smidge of evolutionary psychology.

A conversation that always seems to crop up around this time of year surrounds the question of what makes something scary. A good portion of the time, it boils down to a creator somehow condensing our inherent fear of the unknown (and of helplessness) into a singular expression. However, the more I thought about it, the more I began to doubt whether this General Theory of Fear is sufficient to explain the effectiveness of the best movie monster designs. The exception to this might be Cthulhu, but even so, it’s arguable that the Lovecraftian creation draws his power from that same abstract, conceptual fear than from his actual appearance.

Take away the fact that this is a being whose immensity is impossible to comprehend, and whose very existence breaks the minds of those who witness him, and he just becomes a guy with an octopus for a head and bat wings.

So the question remains: when it comes to those creatures who populate the phylogenetic category labeled “nightmare fuel”, what is it about the way they look that causes such a reaction within us? The fact is, with so much of society’s creature comforts softening the blow of many sources of fear, in order to scare us creature creators must appeal to something much more primal and basic within us.

The Thing That Shouldn’t Be: Evolution and Horror

One of my favorite writers on the topic of psychology is Steven Pinker. A cognitive neuroscience researcher from Stanford, he’s most well-known for his books on the history of human cognition; in particular his book The Blank Slate.

It was there that Pinker contended that humans come into this world anything but blank; instead equipped with a variety of basic survival subroutines that allow us to do things like automatically recognize relevant stimuli in the environment (such as threats or food) and act accordingly without having to waste precious time and calories on conscious reasoning.

A lot of these subroutines (also called schemas) are based off of categorization of objects into groups we can recognize by signature characteristics. We see a creature with feathers, we automatically assume it’s a bird, for example. It’s not a perfect system by any stretch, as any parent will attest to who has had to tell their child not to run up to the ‘big doggy’ (see: horse) and pet it. However, in the Environment of Evolutionary Adaptation (EEA for short), erring in the direction of assuming that is in fact a tiger behind that shrub carries with it much less severe consequences (some acute stress, discomfort) than incorrectly concluding that it wasn’t.

As a result, schemas and expectations following the form of, for example, “this is what a predator looks like”, have survived the evolutionary line because of their usefulness in evading predators and recognizing prey. We expect things like bilateral symmetry, and “know” (see: recognize) what a four-legged animal should move like, and very interesting things start to happen when you violate those expectations.

Let’s say for example that you’re walking in a crowd. Everyone has their own idiosyncrasies in their gait, but on average, people’s movement patterns fall enough into the box of “this is how a human moves” that they barely even register in consciousness. However, if someone’s gait is significantly abnormal (in the strictly statistical sense), such as if they have a bad limp, they’re stumbling drunk, or have a disorder such a muscular dystrophy, they stand out. You notice.

Our perceptual systems have no concept of political correctness, so the hindbrain that first encounters this unusual stimuli starts setting off alarms that “this doesn’t look right. Something’s up.” Typically, this is when our frontal lobes chime, giving us the context to the situation in order to make sense of unusual perceptual stimuli (“Oh, I recognize that. That’s MS. That’s why that person is walking so strangely”).

Now for the fun bit. This is footage of a man walking with muscular dystrophy:

That’s the kind of unusual gait that would stand out, were you to see it in public. Now look at this footage of the famous “Nurses” from Silent Hill: Homecoming

Pretty similar, right? The trick with making that shambling gate into something scary is partially by taking advantage of that violation of expectation. We see an unusual walk, and so we look for an explanation as to why. However, if a piece of disparate information is given to us in setting where nothing ELSE makes fucking sense EITHER like say Silent Hill, it creates this negative feedback loop of fear while our brain frantically scrambles to understand what it’s seeing, and finding no answer, edges closer and closer to full-blown fight-or-flight panic mode.

The assumptions about movement and appearance only make sense because they follow a certain set of “rules” about the world. Part of the reason setting is so important in horror is that it establishes that this is a world that does not follow the same rules as the one we inhabit, introducing that ever-important element of the unknown I mentioned earlier. Placed within scenarios like this (which perpetually keep our sense of reason off-balance), the unsettling effect of something that looks “wrong” gets amplified. Amplify it enough with a combination of tension, timing, and pay-off, and the result is terror.

The Hall of Fame

I think the best way to illustrate this effect is with a couple examples from (in my opinion) some of the best in horror. First, the Pale Man from Pan’s Labyrinth.

On a practical level, there’s little to fear about him. He’s slow, he’s awkward, he doesn’t exactly look strong, and he has to choose between whether to reach for something or maintain depth perception. Despite this, it’s that same awkward, shambling gait (combined with eyes being where they shouldn’t) that sets of alarms in our brains about how biologically wrong this thing is, and by any natural law we know of, should not exist.

But the Pale Man’s power to inflict terror is partially tied to the context he is encountered in. Much like Silent Hill, the banquet hall where Ofelia encounters him is one governed by rules different than the ones that govern our world. Combine this with the fact that the movie is filmed from the perspective of a child, and that this is an enclosed space (the Pale Man would seem much less deadly in an open field), it helps to solidify that feedback loop that sends us spiraling into fright.

The best example of violating biological expectation to generate scares (in my opinion) is John Carpenter’s The Thing; a creature so iconic because it holds no specific, singular appearance. Furthermore, when the shapeshifting horror does take on a specific incarnation, Carpenter seems to take sadistic glee in wreaking havoc on our assumptions of how bodies are “supposed” to be built and function.

Whether it’s blooming tentacle dogs…

eye stalk head crabs…

eye stalk head crabs…

or guillotine jawed rib cages…

or guillotine jawed rib cages…

…The Thing is so scary precisely because it gives exactly zero fucks about what body parts go where. The consequence of this is that the viewer has no idea what to expect from it from one scene to another, readily putting them in the same position as the characters in the film. In essence, this lack of knowledge turns the Thing into a living embodiment of the unknown that we find so chilling.

…The Thing is so scary precisely because it gives exactly zero fucks about what body parts go where. The consequence of this is that the viewer has no idea what to expect from it from one scene to another, readily putting them in the same position as the characters in the film. In essence, this lack of knowledge turns the Thing into a living embodiment of the unknown that we find so chilling.

In a world where halogen lamps and gated communities have sequestered the dark we fear to the periphery of our lives, it’s techniques like these that play off of our most primal instincts. They remind us that no matter how diminutive the unknown is in our daily lives, it’s still there, lurking just out of the corner of our eyes; a reminder our mammalian hindbrains would happily do without.

After all. how can you prepare yourself for something that isn’t possible?

Vince Smith is a writer, podcast host, and dyed-in-the-wool geek of all trades. You can check out other articles and videos by him over at The Rogues’ Gallery, or drop by his Facebook Page, Vincent Smith: Writer, Scholar, Gentleman for other musings from the catacombs of the Internet.

-Written by Vincent Mendoza

If you have a few extra dimes to spare, please help us help a fan in need. Thank you!

If you have a few extra dimes to spare, please help us help a fan in need. Thank you!