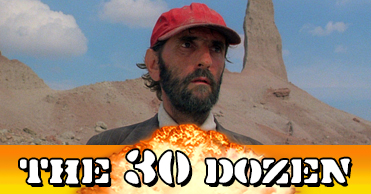

Welcome to The 30 Dozen, a monthly exploration of the films that, like me, turn thirty this year. These are films that have been residing on my must-see list for ages, and those which I’m only now crossing off as together we each approach our third decade on this planet. As I examine one of these movies per month, I hope to glean from each some perspective on my approach of the big 3-0.

Oh give me a home where the Harry Dean roam. Where’s there’s beer and a stack of Blu-ray. Truth be told, this week’s 30 Dozen recruit was scouted not on Blu-ray, but via Hulu thanks to their extensive selection of streaming Criterion Collection entries. Regardless, today we will discuss Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas.

I’ll admit there was a time in which I was quite snobby about venturing into the vast Criterion unknown; seeking out and watching those titles in the collection of which I was not the least bit acquainted. No wait, not snobby. What’s the opposite of snobby? Cretinous. Like some sunken-browed, knuckle-dragging cretin, I would shy away from anything that seemed too arty for my, admittedly sunken-browed, knuckle-dragging cretinous sensibilities. But Paris, Texas is a title that kept catching my eye, if not my full attention. When, upon the tenth cursory glance, I finally noticed that Paris, Texas not only starred Harry Dean Stanton, but was also released in 1984, the time to introduce myself seemed all too ripe.

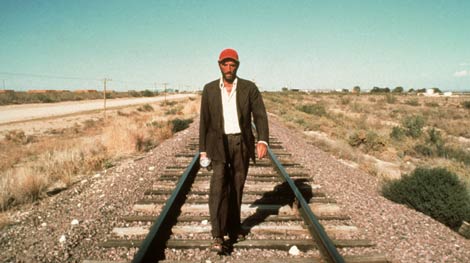

Travis Henderson is a man who wasn’t there, or at least he’s been nowhere for the last four years. When he finally turns up, found wandering in the Texas desert, his estranged brother travels out to recover Travis and bring him to Los Angeles. Travis has a seven-year-old son, Hunter, whom he left with his brother in L.A. those four years ago. After a rocky reunion, father and son embark on a journey to find Travis’ wife, Hunter’s mom, who departed their lives years ago.

It’s not really fair to say that Paris, Texas is a boring film; more appropriate would be to enjoy the manner by which it strolls at its own pace in much the same fashion as our wandering protagonist. There is something so impossibly fascinating about Travis that his directionless jaunts across Texas don’t corrupt the pacing of the film, or at least it didn’t for me. There is an intense seclusion in his apparent psychological crossed-wires, and the designated setting of the majority of this story cannot be more pitch perfect; epitomizing the loneliness of the Lone Star State.

Wim Wenders seems set on making the quintessential anti-cowboy movie. Not that there is anything hateful or vitriolic about his approach, but much of the romanticism of cowboy individualism is stripped away from this Texas-sized deconstruction. So many great westerns feature a mysterious wanderer as the hero, a tacit endorsement of unfettered American freedom. But here, our hero is a man whose wandering carries a price tag of one marriage in shambles and one son without a father.

And he is certainly not insulated from consequence either. He is traveling to Paris, Texas seeking to claim a plot of land he purchased through dubious vendors (bought based on a photograph though he’d never seen it). He walks heavily with pangs of regret and wistful idealizations of family and personal history that only serve to underline the crippling isolation of his need to wander even as he drifts in vain toward a fictive homestead. Travis (whose name is pertinently chosen from the annals of Texas history) seems less Manifest Destiny and more John Milton.

Wenders goes above and beyond to create a cinematic landscape that is both beautiful and, once more in an effort to de-romanticize westerns, poignantly bleak. Before arriving in L.A., Travis tumbles through the tiniest of forgotten hamlets. These aren’t faded, run-down eyesores, but instead pristine, aesthetically-pleasing totems of pure Americana. In true western tradition, these are ghost towns. It’s as if all the inhabitants simply picked up and left one day. Even the score of the film seems aptly wayward; hard, discordant strums of a lonesome guitar. There exists no quaint comfort in those country-western refrains.

When Travis finally does find his estranged wife, in Houston no less, Wenders constructs a scenario in which he must communicate with her through a telephone behind the tinted glass of a private peep show booth; a painful representation of the emotional distance between them. This is where the movie achieves its deepest resonance and where Travis must confront his failings as a family man, culminating in a tremendously bittersweet ending.

So that’s Paris, Texas. And what did this nearly-30-year-old film geek take away from the experience of this long overdue first viewing? Frankly, the lessons afforded by Paris, Texas were not easily accessed. I watched the film, then I watched it again, and then I watched it in pieces. Slowly the full brilliance of the movie began to take hold and it occurred to me that this instilled appreciation would have found no purchase even five years ago. Reviewing Criterion Blu-rays for Digital Noise and its previous incarnation has created a sort of forced expansion of horizons.

I have never been a proponent of classifying detractors of any given film as those who “don’t get it.” It’s an arrogant, reductive cop-out. However, I don’t think a younger me would have “gotten” Paris, Texas. In any event, that little snot certainly wouldn’t have liked it. Yes, it’s arty and methodically paced, but perhaps it’s my expanding film horizon that curbs a resistance to its arthouse flourishes, or maybe my Texas transplantation from the midwest whets my appetite for unconventional takes on cowboy mystique and Lone Star individualism. There’s also the little matter of my three-year gestating obsession with the greatness of Harry Dean Stanton, who gives what I assert is his best performance in this film.

But there’s something else that struck me regarding Paris, Texas as it relates to the pending mortality of my twenties. I’ve been working happily as a film critic/film pundit for several years now, and as has been discussed at length, that career took root thanks largely to the fertile ground of Austin, Texas. I’ve set up my own homestead here, but I would in no way consider myself a fierce individualist. Mama didn’t really let this baby grow up to be a cowboy. Still, there are times when I feel a restlessness pushing me west; specifically to Los Angeles.

The online film criticism industry has been in steady decline over the last couple of years, and even since the last 30 Dozen posting, several unfortunate portents have arisen to signal its total collapse. Sure, we’re sustaining ourselves here at One Of Us, but I’d be a fool to not consider my future. As the big 3-0 creeps closer, I wonder if perhaps it’s time to get serious about screenwriting as the next viable creative avenue. I know what you’re thinking, the number of “aspiring screenwriters” populating the web rivals the number of tumbleweeds in the desert, and I have absolutely no assurance that switching careers would yield results.

However it’s precisely that conflict, that very push against complacency versus the nagging doubt over my ability to write anything worthwhile, that obscures any sense of clear direction. I feel like I’m wandering in Texas, debating endlessly with myself whether one more big step will be required; one more big step west for this not-so-young man. I consider my comfort level residing here in Travis County and contemplate how isolation and emotional severance from everyone I know and love is not a tax I’m keen to pay for tether-less freedom.

For now, I believe I’ve found my own Paris in the desert, and tomorrow is too distant a mirage to dictate the present.